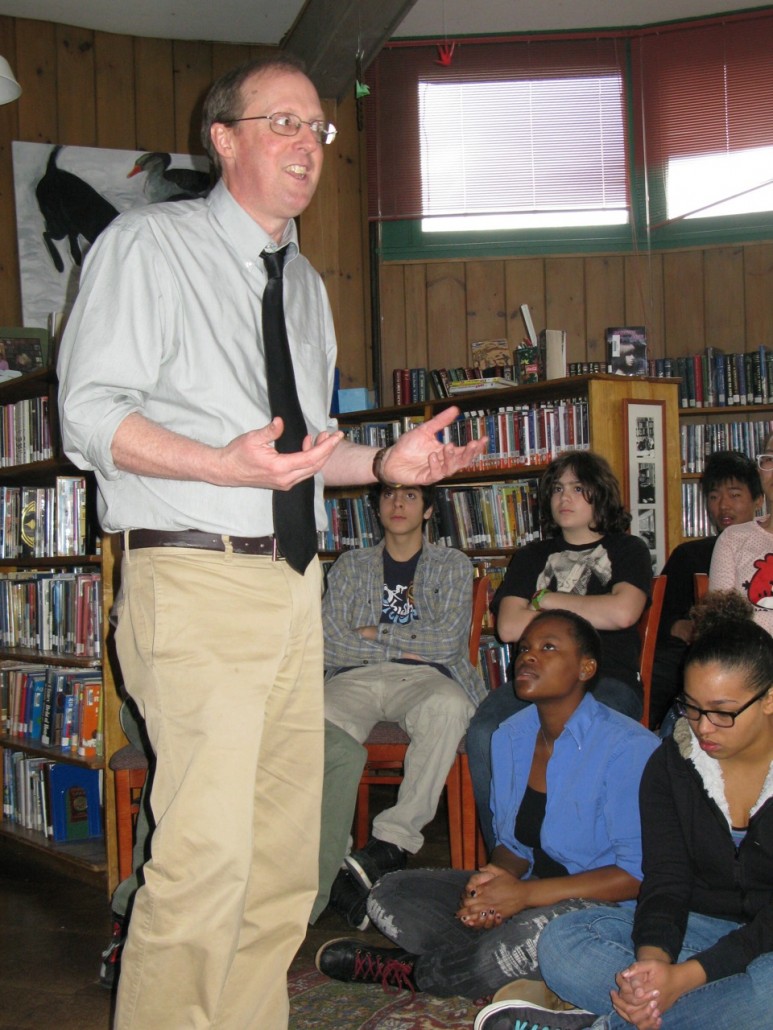

Gary D. Schmidt is a prolific, award-winning author who has received a Printz Honor and two Newbery Honors for his work. He has also completed numerous academic degrees including doctoral studies in Medieval Literature. Yet, as a child, Schmidt was pegged as a poor reader with low prospects and was assigned to the “Pumpkin Group” of students. Here, Schmidt shares what made the difference.

How did you move from being a struggling, reluctant reader to a successful one?

This is an easy one: I had a great teacher. Not long after being put in the Pumpkin Group—the poorest readers—I met Miss Kabakoff, who, in later grades, taught the Track One students—the best students. Somehow, and I don’t know how, she decided that I would come into her class, and when I did, she filled my desk with books. They were way too young for me in terms of grade level, but I struggled with all of them. She spent hours catching me up, and really instilling within me a love of reading. And it all happened very quickly after that: I began reading at grade level, then past grade level, and then reading everything I could on my own.”

You have been faculty in the English Department at Calvin College for 30 years. Your work has been acknowledged with outstanding awards including Newbery Honors, a Printz Honor, and a National Book Award Finalist. In your opinion, what makes good literature for young people?

You have been faculty in the English Department at Calvin College for 30 years. Your work has been acknowledged with outstanding awards including Newbery Honors, a Printz Honor, and a National Book Award Finalist. In your opinion, what makes good literature for young people?

A good story always comes first. All readers—but especially young readers—are attuned to the story that is really a sermon in disguise: that book that is meant to change your behavior into something more along the lines of some current orthodoxy. So a good story first. And with that good story should come honesty about the world, which is not a place where things always end like a Hallmark card, which is not a place where people are one-dimensional, but which is a place where complex characters inhabit settings which are messy and broken.

Many of your books are written to feature historical events and former time periods, and they address topics such as racism and war. Why have you chosen to write meaty books that deal with real-life topics and situations faced by kids of yesterday and today like loss and rites of passage?

It’s an exciting time in the world of children’s and middle-grade and YA literature. There are so many writers doing so many interesting things—and the huge benefit is that everyone brings his or her own skills, perspectives, ways of telling to the table. And I suppose this has always been true of literature: that it can be such a banquet offered to a culture. Today, I read books like the Wimpy Kid books and the Captain Underpants books and marvel at their brilliance. I could never do what these folks do. But I can bring my interests and style and ways of telling to the table, and for me, that means focusing on certain kinds of questions that I think kids are asking—and that they should be asking.

Your books seem to start quietly but are so emotionally charged. What is your process for developing such intense stories? Do you purposely bury details which require the reader to dig in?

I tend to write for middle-grade readers, and in writing about those years, it seems to me I am writing about a very intense time in our lives. It’s a time when a kiddo is beginning to leave childhood, and look at the intensity of that leavetaking: suddenly, the kiddo is thrown into a world filled with others who, like herself, are trying to understand who they are in every way we can imagine: socially, intellectually, politically, economically, religiously, aesthetically. The kiddo’s own body is acting bizarrely. And in all this, the middle-grade kid is taking on all sorts of new identities and perspectives as he grapples with new ideas, new social relationships, and the startling realization that she can have ideas and beliefs that are truly her own instead of those of parents and peers. It’s an intense time. So I do want to depict that. As far as process, again, story has to come first. I want a story that is set in that intensity, and that depicts the complexity of a middle-grade kiddo’s world. And as a storyteller, of course I am shaping that experience, because I am not writing a transcript, but a novel that does not imitate life in its exactitude, but in its essence and meanings. So yes, details are buried early on that will come to fruition later in the story—hopefully with greater meaning than when the reader first encountered them. Liza Ketchum, from whom I have learned a great deal as a writer, calls these endowed objects—and I think there can be endowed actions as well.

Orbiting Jupiter (Clarion Books, 2015) was published in October. It is a most unique, yet beautiful, tale with several storylines woven within. Where did this story come from?

Orbiting Jupiter was inspired by a kiddo I met in a juvenile prison, though this is not his story in any way. It was also inspired by a 13-year-old boy I read about years ago. He lived in Arkansas, I think, and at age 13 had had two children. It’s perhaps not as remarkable as we think, but it struck me at the time that he now has to think about this quandary: He is a father, and he is also a middle-grade kid. Is it possible to live both roles in any meaningful way? That seems to me a really interesting question, and one that might be best answered in the context of a story.

Do any of the characters in your books reflect you?

I am beginning to wonder if, in fact, all of a writer’s characters are, in some way, reflections of the writer. This does not mean that the writer is always writing autobiography, but it might mean that the writer is always working out those things that are critical to him or her. So, in many ways, yes—Holling is me, or I am Holling (The Wednesday Wars, Clarion Books, 2007). But I also think there is much in Doug (Okay for Now, Clarion Books, 2011) that is me, and in Jack and in Joseph (Orbiting Jupiter). That’s why the beginning of Walden (Ticknor and Fields, 1854) always strikes me as so true: Thoreau insists that he will talk about himself because who else does he know better?

What do you wish others knew about you? Is there a question you wish interviewers asked?

Is there a question I wished interviewers asked? What a good question. But in the end, I’m sorta this private guy and a Calvinist to boot, and there isn’t too much I’m all that eager to trot out! I have too much New England blood for that.

What you are working on or what we can see from you next?

I have three picture books written with Elizabeth Stickney that are finished, and am working on a picture book with Phyllis Root on the writer Celia Thaxter. I’m currently working on the next two novels, both within the Wednesday Wars universe. And—since I also like to work on academic books—I’m finishing a book on three New England historians who wrote during the 1790s—the kind of book that won’t exactly hit a bestseller list, but that I learn a great deal from.

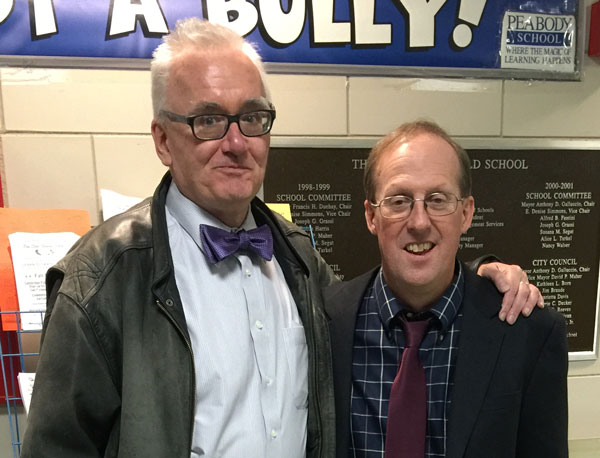

Roger Sutton, Editor in Chief of The Horn Book and Gary D. Schmidt

How can teachers, librarians, and parents best use your books to encourage young people to not only read, but also to engage with what they are reading?

I think all good stories ask questions; if they don’t, then okay, you’ve had a beach read—and that’s fine occasionally. But a good story must ask questions—and sometimes very hard questions. That’s the difference between To Kill a Mockingbird (J.B. Lippincott, 1960) and some faddish book that gets made into a slick movie and then disappears. So to engage with a book, a reader needs to engage with the questions that book poses. I think that so many extraordinary books today pose questions that a young reader grapples with: Rick Riordan’s questions about how a kid comes to new understandings about who he is, or Ron Koertge’s novels about kids grappling with definitions that they have been burdened with, or Linda Urban’s funny books that ask how a kid comes to authentically take on new roles, or Walter Dean Myers’ books about kids facing a larger culture that might be hostile. To engage with a book is to engage with the questions the author is asking.

What is the best way for readers to connect with you?

Best way to reach out is through a letter. No kidding. A real, honest-to-goodness letter that arrives in an envelope and that I open and read and then answer with another real, honest-to-goodness letter. I am not active on social media. There’s a Facebook page set up by one of my students and now managed by my daughter, but I’ve never been on it. I have done the occasional Skype thingy, but have never liked the format. You’re so distanced from the people you are talking to, it feels cold. I know: I’m a dinosaur.