The newest National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature is not a novelist. He is not a poet. He does not create picture books, in the traditional sense. Gene Luen Yang does not fit nicely in a box like many other award-winning, notable authors do. He is an Asian American comic book creator, and he is on a mission to push kids out of the La-Z-Boy® and into literature.

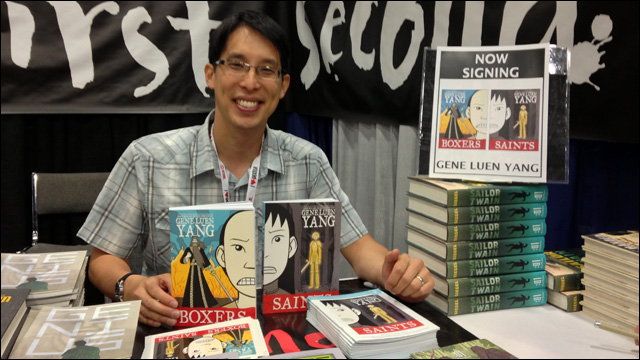

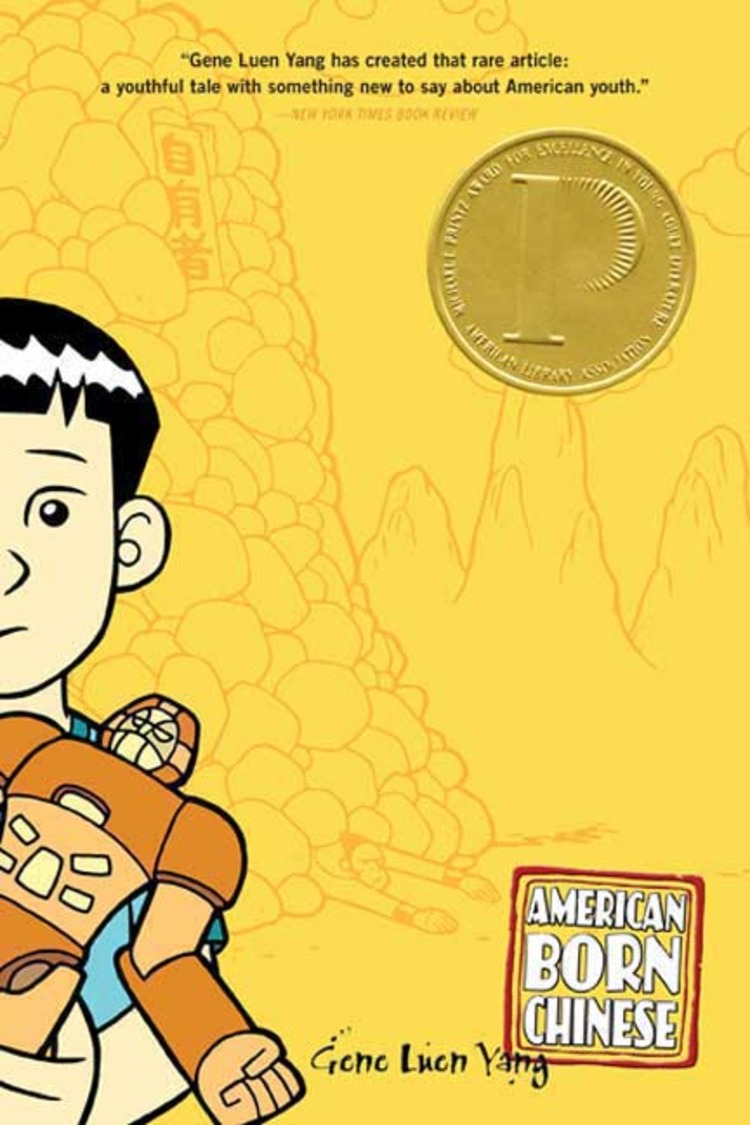

Yang’s American Born Chinese (First Second Books, 2006) was the first graphic novel to win the Printz Award and the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award. His two-book set Boxers & Saints (First Second Books, 2013) was also a finalist for the National Book Award. Yang follows Kate DiCamillo as National Ambassador and has this to say about his plan

Yang’s American Born Chinese (First Second Books, 2006) was the first graphic novel to win the Printz Award and the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award. His two-book set Boxers & Saints (First Second Books, 2013) was also a finalist for the National Book Award. Yang follows Kate DiCamillo as National Ambassador and has this to say about his plan

“My platform, Reading Without Walls, challenges young people to read outside of their comfort zones. The Children’s Book Council, the Library of Congress, and I have put together some material to support librarians and teachers who want to issue the Reading Without Walls Challenge to their students. Specifically, I want kids to do this challenge in one of three ways:

- Choose a book about someone who doesn’t look or live like them.

- Choose a book about a topic they might find intimidating.

- Choose a book that’s in a format they don’t normally read for fun. This can be a graphic novel, a prose novel, a picture book, or a book in verse.”

In past years, it was a challenge to find books featuring a diverse cast of characters. But with the We Need Diverse Books campaign becoming more influential, and with the broadening base of diverse authors and illustrators, classroom and library shelves now feature a variety of excellent choices. Yang, a member of the campaign’s advisory board, believes this change is a good thing:

“Stories ought to be experienced in community, because they’re often expressions of community. And that’s why libraries and librarians are so important. They are community for children who otherwise have none.”

“As American readership gets more and more diverse, it’s natural for us to want more diverse stories. The We Need Diverse Books agenda is this: We want our stories to more accurately reflect our world. Our world’s heroes come from every sort of background imaginable. The same should be true of the heroes of our books.” Many of Yang’s books seem to focus on the Asian American experience and the challenges involved in discovering and accepting cultural identity. However, he is not writing specifically to or for Asian American kids—rather, he is writing primarily to develop empathy in readers from any background.

“When I’m writing, my primary goal is to keep my reader with me from the first page to the last. I don’t really think about the reader’s background too much. Stories develop empathy. A good story is an empathy workout. We need to build empathy for every member of society, especially those at the margins. That said, I really do want to see better representation of Asian Americans in American media. We’re often left out of the American conversation about race.”

With at least one of his latest projects, Yang continues to keep Asian Americans front and center.

“Right now, I’m working on a few different projects. Secret Coders is a series of middle-grade graphic novels that teaches kids how to code computers. I’m working on that with cartoonist Mike Holmes. The second volume [of that series], Paths & Portals (First Second Books, 2016), was released on August 30. I’m also doing the next installment of the Avatar: The Last Airbender series from Dark Horse Comics with Studio Gurihiru. And I’m writing New Super-Man for DC Comics. This is a monthly series about a kid in Shanghai who becomes the Superman of China. The art is by Viktor Bogdanovic, Richard Friend, and HiFi Color. Finally, I’m writing and drawing my next graphic novel, a nonfiction book about a high school basketball team that I followed for a season. This is going to be a long one, and it will be titled Dragon Hoops (First Second Books, 2018).”

Comics vs. Graphic Novels

“The term ‘graphic novel’ began as a way of separating comic books from the genres—superheroes and funny animals—that had dominated them for decades. The folks who popularized the term wanted to show that you could use illustrated panels to tell any sort of story you wanted. And I have to say, the effort has largely worked. But to my mind, ‘graphic novel’ and ‘comic book’ are essentially the same thing. I sometimes define graphic novel as a comic book that’s thick enough to need a spine.”

“Some people do find reading comics hard, and I get that. You use one part of your brain to process the pictures, another to process the words. What I say to these folks is, don’t be afraid to take it slow. Don’t be afraid to read pages over. And spend some time enjoying the art, because the artist spent a lot of time making it.”

Are Graphic Novels Too Graphic?

“Reluctant reader settings are a great place to introduce comics into a school community, but they’re not the only place comics belong. For example, many teachers have found success using comics to teach visual literacy. The interplay between words and pictures can be very complex. Getting students to think critically about the images in a graphic novel can help them think critically about the images in the media that surround them.”

“We live in a world that’s full of both wonders and horrors. Our children do, too. I’m a parent of four children and my parenting style tends toward paranoia, so I totally understand that deep, primal need to keep kids safe. But ultimately, perfect safety is impossible. Our main task as parents is to teach our children to deal with the world as it is, not as how we want it to be.

“Books, including graphic novels, play an important role in that task. The horrors in stories like Maus (Pantheon, 1991), March (Top Shelf Productions, 2013/2015/2016), and Boxers & Saints (First Second Books, 2013) are all real-world horrors. They’re a part of our history and our children’s history. Our children have to know their history.

“That said, I do believe in scaffolding, in building bridges between young people and difficult material. My four children can have vastly different responses to the same book. They need different levels of scaffolding.

“I know this is idealistic, but my hope is that when a young person encounters something difficult, whether it’s in a prose book or a graphic novel or a movie, they’ll have someone in their community with whom they can process. Stories ought to be experienced in community, because they’re often expressions of community.

“And that’s why libraries and librarians are so important. They are a community for children who otherwise have none.”

More About Gene Luen Yang

According to his mother, Yang began drawing when he was two. Yang’s first memories of drawing came a little after that, however.

“I remember when I first figured out how to draw the five-pointed star. I’m not sure how old I was… four, maybe? But it was a big deal because stars are freaking complicated. I remember drawing stars on every piece of paper I could lay my hands on, and then bragging to my older cousins. They were not impressed.”

In fifth grade, the budding artist started making comics. And in his early 20s, Yang began self-publishing his work under the moniker Humble Comics while working as a high school computer science teacher.

“I originally wanted a cool name like ‘Space Monkey Comics’ or something, but I was having a lot of self-esteem issues. Specifically, my self-esteem was attached to how well or poorly I drew. And as I got into the comics industry, I met cartoonist after cartoonist who could draw the socks off of me. I just started feeling bad, you know? A priest at my home church used to say that humility and truth are the same thing. If you take a truthful look at yourself and your place in the world, you’ll feel humble—and grateful, too. The name Humble Comics was meant to remind me to look at myself truthfully. The self-esteem issues have gotten less intense as I’ve gotten older—mostly because I’ve gotten too tired to keep up that sort of intensity—but they’re still there. I think it’s just a lifelong thing.

“Anyway, I began as a self-publisher. I used to photocopy comics at the local copy store, staple them by hand, and then sell them through local comic book shops and at conventions. ‘Comic Relief’ in Berkeley was the first store to carry my comics. Eventually, publishers started to notice me. I signed on with First Second Books after about 10 years of self-publishing comics. A lot of folks in middle grade and YA graphic novels have similar career paths: Raina Telgemeier, Kazu Kibuishi, Jason Shiga.” In 2014, a year after Boxers & Saints made its debut, Yang left his teaching post to pursue drawing and writing full time.

“Anyway, I began as a self-publisher. I used to photocopy comics at the local copy store, staple them by hand, and then sell them through local comic book shops and at conventions. ‘Comic Relief’ in Berkeley was the first store to carry my comics. Eventually, publishers started to notice me. I signed on with First Second Books after about 10 years of self-publishing comics. A lot of folks in middle grade and YA graphic novels have similar career paths: Raina Telgemeier, Kazu Kibuishi, Jason Shiga.” In 2014, a year after Boxers & Saints made its debut, Yang left his teaching post to pursue drawing and writing full time.

“I’m a cartoonist, but on some projects I call myself a writer because someone else handles the art. When I both write and draw, I have complete control over the project. Every word written and every line drawn comes from me. There’s something very satisfying about that. When I collaborate, I give up some of that control, but in return I get someone else’s vision. The final product becomes a melding of visions, mine and my partner’s. Almost always, it surprises me in fun and interesting ways. Almost always, it turns out better than I’d imagined in my head. There’s something very satisfying about that, too.

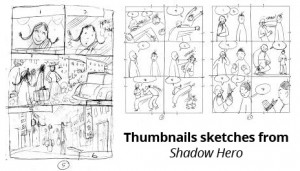

“When I first started making comics, I would make my stories up as I went along. That didn’t work so well. My characters would end up in these corners, and I would have no idea how to get them out. Eventually, I moved to outlining, which means I write a short summary of the entire story before I start on the script. When I’m drawing, I do lots of thumbnail sketches before starting on the final art. Similar concept. I need to carefully plan things out. For me, the battle is often won or lost in the planning.”