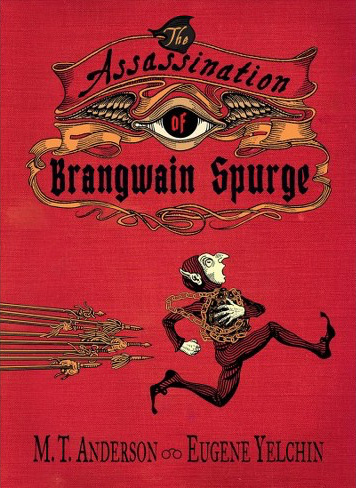

The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge (Candlewick, 2018) is perhaps one of the most revolutionary novels introduced in recent years. The story is an illustrated allegory as well as a political satire with egocentric characters, cultural misunderstandings, and viewpoint contradictions—all forcing the reader to read and reread to determine what is truth and to consider how the story reflects current events and trends.

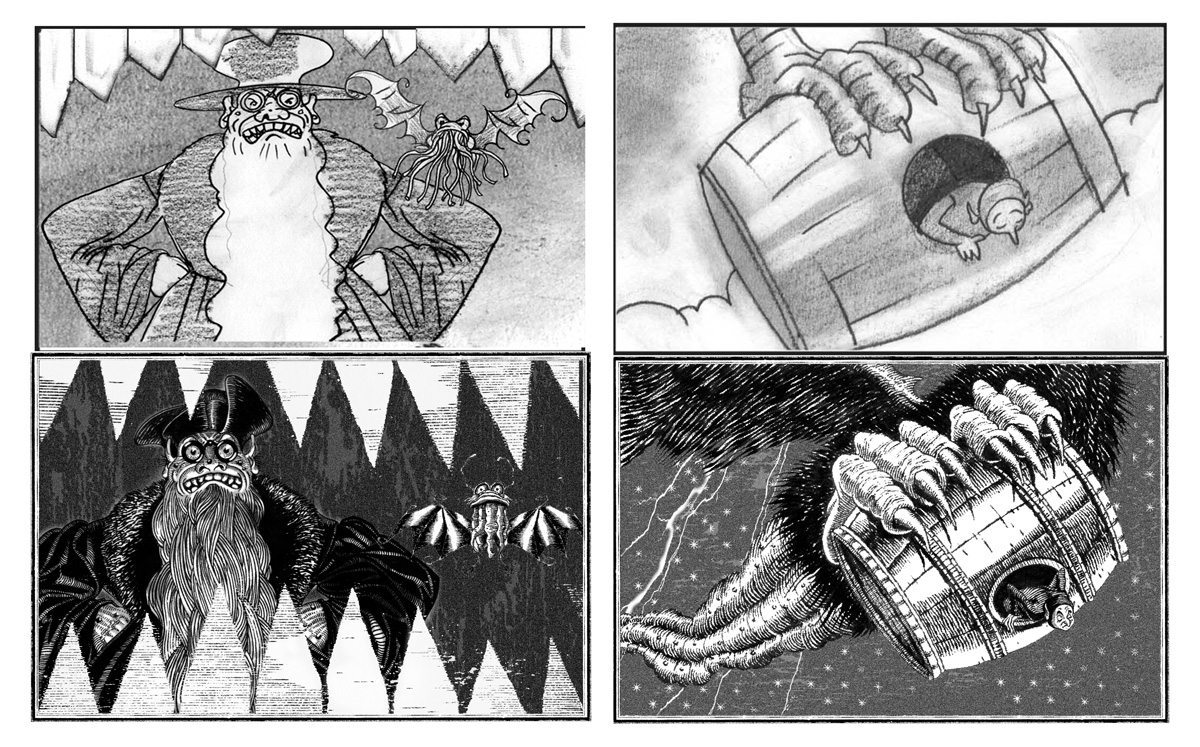

This is the story of Brangwain Spurge, an elf historian with a superiority complex, who is sent on a mission to the land of the goblins supposedly to present a peace offering while spying on the enemy. In the novel, Spurge “tells” his side of the story through black-and-white images drawn by Newbery Honoree Eugene Yelchin. There are two other storytellers in the book: the goblin archivist Werfel, Spurge’s counterpart and host in the neighboring land, and Ysoret Clivers, Spurge’s boss back home and a ranking member of the elves’ Order of the Clean Hand. Their perspectives are written by National Book Award winner M. T. Anderson with each perspective differing from—and contradicting—the others.

This is the story of Brangwain Spurge, an elf historian with a superiority complex, who is sent on a mission to the land of the goblins supposedly to present a peace offering while spying on the enemy. In the novel, Spurge “tells” his side of the story through black-and-white images drawn by Newbery Honoree Eugene Yelchin. There are two other storytellers in the book: the goblin archivist Werfel, Spurge’s counterpart and host in the neighboring land, and Ysoret Clivers, Spurge’s boss back home and a ranking member of the elves’ Order of the Clean Hand. Their perspectives are written by National Book Award winner M. T. Anderson with each perspective differing from—and contradicting—the others.

The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge is a compelling and ambitious read as one must decipher truth from deception and ascertain what is really happening over the course of more than 500 pages. The book is the brain child of Yelchin who was fascinated with the idea of a story being told from two opposing points of view, and, in his mind, that meant two authors. “I have always been a great admirer of M. T. Anderson’s work, for his courageous experimentation and attention to form,” shares Yelchin. But the two authors had never met in person and lived on opposite sides of the country. However, when Anderson was in Los Angeles to present a lecture, Yelchin seized the opportunity to pitch his idea over lunch. “I asked him to join me in this experiment, and his insatiable intellectual curiosity prevented him from refusing.”

“Some time ago, I became interested in the idea of an illustrated text, in which the illustrations, instead of illuminating the text, would contradict it. The written language and the pictorial language would be in a kind of a ‘battle.’ As a result, the story had to be told from two opposing points of view, which meant having two protagonists instead of one and, ideally, two authors.”

Yelchin, born and raised in the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, and Anderson, born and raised in the United States, were perfect co-authors for a project involving different perspectives. But both had a common interest—high fantasy and the world of elves and goblins. And both agreed younger readers would make the perfect audience for the book. “We knew that young readers would come to such narrative with certain genre expectations, which would be incredibly fun to subvert. Additionally, it would be easier for us to slip in much larger thematic concerns under the cover of a familiar genre.”

Yelchin, born and raised in the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, and Anderson, born and raised in the United States, were perfect co-authors for a project involving different perspectives. But both had a common interest—high fantasy and the world of elves and goblins. And both agreed younger readers would make the perfect audience for the book. “We knew that young readers would come to such narrative with certain genre expectations, which would be incredibly fun to subvert. Additionally, it would be easier for us to slip in much larger thematic concerns under the cover of a familiar genre.”

So the two set out to collaborate from different coasts on a book about a fantasy world. “Obviously, writing a book with another person via e-mail dispatches is tricky,” Yelchin admits. “Telephone conversations were of great help, but it took a number of drafts to work out the logic of the narrative.”

Eugene Yelchin’s art and writing studio

The process the two authors chose to use when creating The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge was built on an action and reaction model. “Anderson would write a chapter from Werfel’s point of view, and I would draw a chapter from Spurge’s point of view, and then we would exchange the chapters to review. I would react to his writing, and he would react to my sketches. In that way, we inspired each other and kept moving forward. Perhaps this process required more work than was necessary, but it was not really work. It was fun.”

“The most fascinating part of our collaboration was the fact that M. T. Anderson and I have very different cultural backgrounds, and as such we were perfectly suited to play characters with very different cultural backgrounds. In other words, we had to overcome our individual preferences in order to find a common language, which is exactly what this book is about.”

During the course of their discussions and collaboration, both Anderson and Yelchin found their own perspectives and pasts creeping into their work on the manuscript. “We reveal ourselves on the page whether we like it or not,” says Yelchin. “For that reason, my conversations with Anderson about goblins and elves kept swerving toward the Cold War. I had experienced it personally behind the Iron Curtain. Anderson had explored it brilliantly in his Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad (Candlewick, 2015). We had a lot to talk about.”

The book is full of fantastical descriptions, stark imagery, and dark humor. Yet, it also features themes of friendship, awakening, and personal growth, the latter illustrated by the idea behind the goblins shedding their skins. “During the course of our conversations, Anderson had this astonishing idea that goblins shed their skins to preserve them as mementos of their lives’ passages. As a result, I drew the epilogue sequence in which Brangwain Spurge, who initially finds this skin business repulsive, sheds his own skin. This visual metaphor brings the character’s arc to its most surprising yet logical conclusion. But it also feels personal to me. Like Spurge, I had to work very hard to shed my Soviet skin.”

Preliminary pencil sketch and the finished art for chapter 6 on the left and for chapter 4 on the right

Yelchin cites the epilogue as the most meaningful section of the book, but acknowledges that the entire book was personal. “In the USSR, my own character was formed in the environment devoid of truth. Truth was dangerous. To create the text, in which the act of reading words and looking at the pictures is the act of searching for truth, is so similar to my own path in life that I find the book enormously rewarding even though I only did half of the work.”

Yelchin is not the only person who identifies with the characters and message of The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge. Prestigious award committees and readers of all ages can’t stop talking about the book. In fact, it was a finalist for the 2018 National Book Awards for Young People’s Literature.

“I was born and raised in the former Soviet Union during the Cold War. My fantasy was our glorious Communist future, my dystopia — our everyday reality. Since every single book for young readers published in the Soviet Union was shot through with the Communist dogma, I began reading Russian 19th-century classics for grownups fairly early. Perhaps that is the reason why I can’t seem to aim at a specific age group while making a book, but try instead to make a book that, as a young boy, I would have been thrilled to read.”

Though flattered, Yelchin is taking the accolades in stride. “It feels great, of course, how can it not?” asks Yelchin. “This book is an experiment. We had no idea how it would be received. I do not believe we have even spoken about it; that was not our concern. Our concern was: Could we pull off this weird experiment and by what means would we do it? The fact that the book is being received well is encouraging. The positive reaction feels like a permission to continue experimenting, to make books that are not confined by conventions or by expectations of what books for young readers must be.”

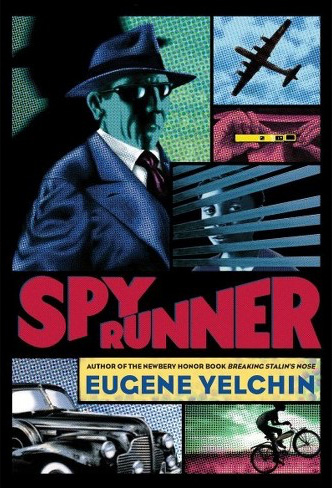

In his next books, Yelchin continues to explore the themes of the Cold War and espionage as well as Russian characters. In February 2019, Yelchin’s new middle grade novel Spy Runner (Henry Holt and Co.) will be published. “On the surface, Spy Runner is a Cold War spy thriller jam-packed with secrets, suspense, and description; but just below the surface, the book examines the fragility of democracy in the times when a particular portion of our population was deemed dangerous or unworthy of being called Americans.” He is also working on a dramatized and heavily illustrated autobiography, Watching Baryshnikov From the Wings.

In his next books, Yelchin continues to explore the themes of the Cold War and espionage as well as Russian characters. In February 2019, Yelchin’s new middle grade novel Spy Runner (Henry Holt and Co.) will be published. “On the surface, Spy Runner is a Cold War spy thriller jam-packed with secrets, suspense, and description; but just below the surface, the book examines the fragility of democracy in the times when a particular portion of our population was deemed dangerous or unworthy of being called Americans.” He is also working on a dramatized and heavily illustrated autobiography, Watching Baryshnikov From the Wings.

In each of his projects, Yelchin is driven by point of view. This was especially apparent in The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge. Why is this such a critical theme for him? “While looking at the same thing, many of us will see something different. Many of us will see what we want to see and will be blind to what makes us uncomfortable. Many of us will see with someone else’s eyes, either unsure of our personal visions or thoroughly influenced by the visions of others. To see with our own eyes is remarkably difficult. To trust our personal points of view and to live our lives accordingly, to honor others’ points of view and have them honor ours, is what true freedom means to me.”