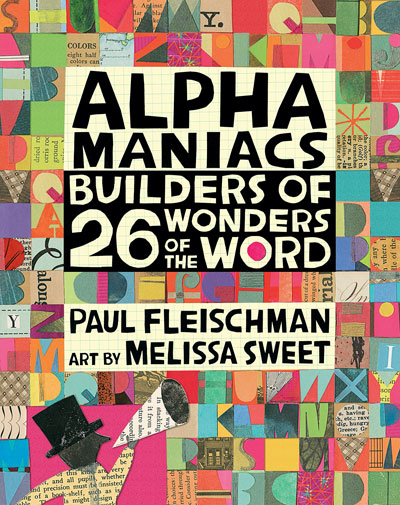

Newbery Medal-winning author Paul Fleischman and Caldecott Honor-winning illustrator Melissa Sweet have collaborated on a unique tribute to language and those who lovingly and imaginatively tinker with it in Alphamaniacs (Candlewick Studio, 2020).

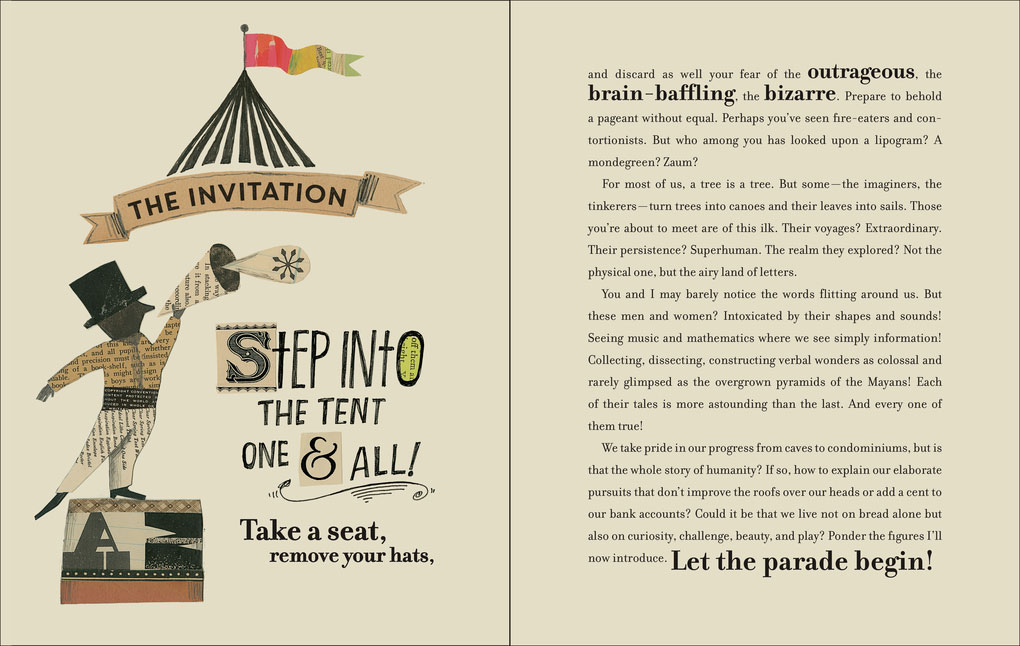

Though difficult to classify, Alphamaniacs is a circus-themed volume of stories highlighting 26 individuals, one for each letter of the alphabet, who have contributed to, transformed, and played with language. It is chock full of little-known but fascinating characters and full-color, detailed collage illustrations all celebrating the foundation of language: the word. The entries explore word-based poetry, art, microbook creation, and even the development of the Klingon language. Here, Fleischman and Sweet share a bit about the book and about themselves.

As an award-winning writer for children and young adults, how did you come up with the premise for Alphamaniacs?

Paul Fleischman (PF): Books, like rivers, have multiple tributaries. At age ten I opened the cover of Ounce, Dice, Trice by Alastair Reid (New York Review Books, 2009), and my life was changed forever. The book had lists of suitable names for whales, unusual terms for times of day, words that sounded like counting from one to ten—ounce, dice, trice, quartz, quince, sago, serpent, oxygen, nitrogen, denim—and other evidence that language could be a playground rather than strictly a classroom subject. When my parents brought home a hand printing press one day, I began learning about the purely visual side of language, which eventually led me to the calligrapher Mike Gold. I was always drawn to music and was riveted when I found out about Ernst Toch’s Geographical Fugue in high school. Years later, when I read about Georges Perec’s novel without the letter e, I decided to gather these linguistic explorers together.

A young Paul trying out his dad’s desk and pipe

Why did you cast the book as a circus performance?

PF: The book originally wasn’t a book, but a play for adults. This allowed for Geographical Fugue and many other of my subjects’ works to be performed. Because their pursuits would strike most people as bizarre—spending decades trying to find the source of OK or subtracting words from Emily Dickinson’s poems to reveal an entirely different set of poems within—a circus sideshow seemed the perfect conceit. The cast of four was headed by a whip-wielding ringmaster who added narration as needed.

What was your criteria for those who made the cut?

PF: I gave myself the sort of constraint Georges Perec would have liked: twenty-six figures, one surname for each alphabet letter. So aside from having done unusual things with language, my subjects needed the right sort of last name. This made the selection much tougher. I probably spent ten years gathering my cast, constantly making substitutions as I learned of new candidates. When I converted the play to a book, my editor suggested removing the constraint, which turned out to be a great idea that both allowed a better order and opened the book to new subjects—miniature book master David Bryce and language rescuer Jesse Little Doe Baird, for instance.

Introducing…

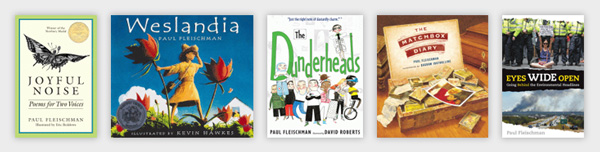

Paul Fleischman is the author of many books for children, including the Newbery Medal–winning Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices. With Candlewick Press, he is the author of Weslandia, The Dunderheads, The Matchbox Diary, and Eyes Wide Open. He lives in Monterey, California.

Melissa Sweet has illustrated nearly one hundred books for children, including the Caldecott Honor books The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus and A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams. With Candlewick Press, she is the illustrator of Baabwaa and Wooliam and Firefly July: A Year of Very Short Poems. Melissa Sweet lives in Rockport, Maine.

As a Caldecott Honor-winning artist, how did you approach the Alphamaniacs project? It is quite involved, so clearly it took planning on your part.

Melissa Sweet (MS): To my mind, the most important thing to find out is someone’s process: What did they do, how did they do it, and can I isolate the moment when they had their idea? What led to that moment? In illustrating someone else’s manuscript, it takes time to know the material well enough to begin the art. If the book is nonfiction, I begin by researching the subject in any way that feels pertinent: traveling, reading, talking to people. All of that information helps me decide on the materials and how to render a story.

Using Paul’s bibliography as a starting point for Alphamaniacs, I bought used books and read about each person, or bought the book they wrote, or both. I’m looking to glean something about them: a quote, a material, a way of working that inspires the art. One of the things I love about Alphamaniacs is how quirky each person’s idea was. They gave themselves constraints, like writing a novel without the letter “e,” or inventing a language for fictional people like Klingon.

In Alphamaniacs, like many of your books, you use a significant amount of text as part of your illustrations. This technique seems especially apropos considering the topic of the book. Are these from newspapers or other books?

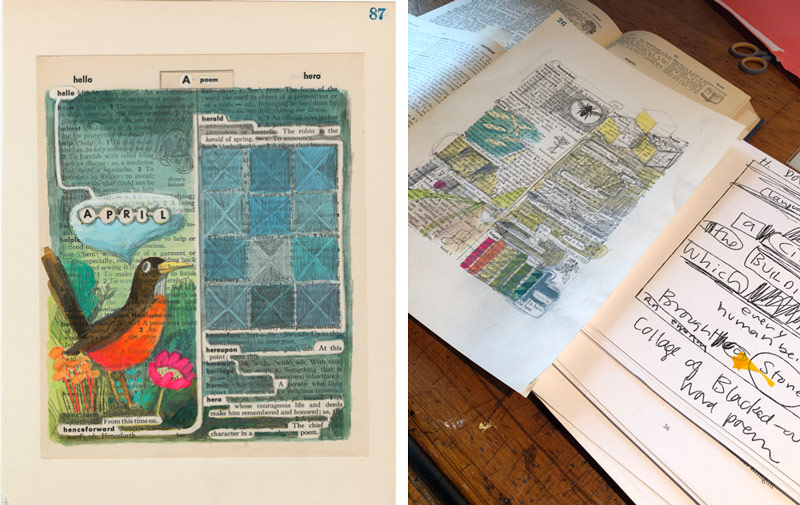

MS: Many of the big letters I printed at a letterpress studio. All of the text comes from old books, old typeface foundry books, or else I print with small woodblock type. My studio is bursting with paper.

Melissa Sweet in her studio

Is it true you assemble all of your collages by hand rather than on the computer?

MS: It is true that everything is done by hand. The art is photographed or scanned before sending it to the publisher.

Out of all 26 alphamaniacs highlighted in Alphamaniacs, do either of you have favorites?

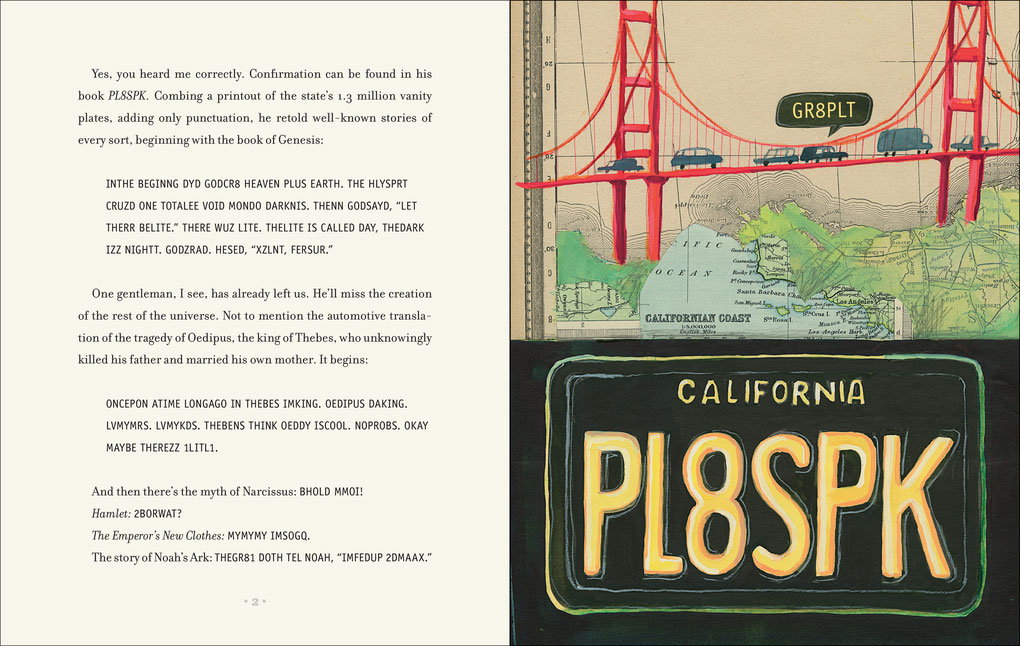

PF: I love them all, as well as the hundreds of runner-ups I considered, but a few do stand out for me. Mike Gold is one, the calligrapher who came up with a thousand different a’s, which I think should be published as a testament to human creativity. Daniel Nussbaum and his retelling of the classics using California vanity license plates is another. Jean Dominique Bauby, who dictated his eloquent memoir solely by blinking an eye—the only muscle he could control. And Ludwik Zamenhof, who tried to bring peace to the world through his universal language.

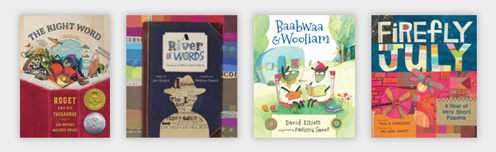

MS: My favorite is Doris Cross who created “found” poems using old dictionary pages and crossing out or painting over the words she didn’t want, creating something new and surprising. I bought a vintage dictionary just like Cross used to recreate her process. One could decide to “illustrate” a book like this with an object from each person’s life, but in reinterpreting what they did with collage, my intention is to give the book a visual vibrancy and accessibility.

Like Father, Like Son

Your father, Sid Fleischman, won the Newbery Medal in 1987. You followed with a Newbery Medal of your own two years later. Is his influence to be found in Alphamaniacs?

PF: He saw a circus sideshow as a kid, was entranced, and decided that someone else could be President—he was going to become a magician. Which he did, traveling the country during the last days of vaudeville. When he turned to writing, he drew on his performance background, crafting scenes and plots to keep readers enthralled. From him I learned that history is fascinating, that laughter is one of the boons of being alive, and that imagination is limitless. I revived him in the good-humored master of ceremonies at the center of Alphamaniacs.

Reluctant Reader, Eager Artist

On your website you mention you were a bit of a reluctant reader and preferred looking at the pictures in books. Have you come to fully enjoy reading or do you still prefer the illustrations?

MS: Growing up I was (and still am) a maker in every sense. I preferred figuring things out and using my hands to reading, mostly because there was so much else to do. We had a neighborhood of kids and were all expected to make our own fun.

If I could pinpoint when a switch was flipped and reading became a big part of my life, it was when I began working on picture book biographies. Learning how to research and bring someone’s life to the page made me think differently about how I made art. That was when I discovered putting words within my art is exactly what I love to do. Now, one of the best parts of my work is all the reading I get to do in preparation to illustrate a book.

Fans must surely contact you both regularly about your work. What ideas and inspiration can you share for using your book in schools, classrooms, libraries, and homes?

MS: An easy and fun exercise is making blackout or whiteout poems. Paul mentions A Humament, which I recommend to see the possibilities: http://www.tomphillips.co.uk/humument

Start with any text pages, newspapers, discarded books, catalogs—anything goes and there are no rules. Finding a poem is guaranteed.

The people in Alphamaniacs play with the idea of constraint and breaking rules at the same time. Surrealist word games have similar ideas: https://artclasscurator.com/surrealist-games/

I once created a picture book with words from A to Z that I wrote at random called Carmine: A Little More Red (Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourts, 2008). It was fantastic fun. Have an alphabet scavenger hunt in your home, neighborhood, library, or museum. Keep a notebook of 26 words that begin with A to Z. Can a story or poem be written from those words? Illustrate it with letters or words cut out from magazines.